1849 western literary messenger

The Western literary messenger, Volumes 12-13, Buffalo, 1849

From the Buffalo Commercial Advertiser.

Sketches and Incidents from abroad

[BY THE LATE EDITOR]

NUMBER II

Arrival at Kingston - The Bay &c., &c.

Kingston, Jamaica, Nov. 16, 1849.

As

we rounded the Cape, and bore up S.E. by E., for Jamaica, we met the

trade wind, blowing almost a gale, and raising a heavy sea. This lasted

until we got under the lee of the island, Saturday night. Sunday

morning, when I went on deck, the sun was shining brightly - his fierce

rays rendered tolerable by an awning and a gentle breeze - and our ship

was gliding as quietly and smoothly over the ocean as if she had never

known a storm, and had not the day before been deluged with the seas

that broke over her deck. The coast was low and part of it marshy, but a

few miles back the land rose boldly into mountains of the most varied

and picturesque forms, clothed with a tropical luxuriance of vegetation

to the very summits. With the passage of every headland, new views were

opened more beautiful, if possible, than those left behind. At 11

o'clock the ship's bell was rung for morning service, and passengers and

crew - the latter making a very smart appearance in their neat blue

jackets - assembled in the dining saloon, where the impressive service

of the Church of England was read by the Captain, with a solemnity and

propriety of elocution I have rarely known surpassed. It was about an

hour before sunset when we rounded a bold point, and the Bay of Kingston

lay before us. The Bay forms nearly a semi- circle with a diameter, as I

should judge, of six or seven miles. Sweeping around it, at the

distance of from one to four or live miles from the water - though, such

was the transparency of the atmosphere, they looked but a musket shot

off - is a range of mountains of forms even more picturesque than those

we had seen during the day, and rising into peaks, some of which, in

sight, were four or five thousand feet high. I did not perceive, as some

voyagers have alleged, that the air was loaded with the perfume of

flowers and the fragrance of spices and aromatic shrubs; but it needed

not such to make the scene truly enchanting. The water of the bay was as

smooth as a mirror. The vegetation on shore was of vivid green. Cocoa

trees waved their long plume-like foliage in the dying breathings of the

sea-breeze. The mountains gleamed in roseate purple, blue or green, as

they were more or less covered with vapor, and at other points, where

the exhalations of the day had condensed into soft showers, half way up

their sides, rainbows spanned like an arch of glory the portals of some

dark ravines.

The sun was sinking as we came up the bay, and broad shadows were

falling on its bosom. We passed rapidly by the little town and

fortifications of Port Royal, and directly over the spot where, many a

fathom down, is old Port Royal, so famed in the annals of the

Buccaneers, and so awfully overwhelmed in the great earthquake of June,

1692, when, as if its wickedness could no longer be borne, the earth

gaped and swallowed it. For many years after, when the water was still

and clear, the remains of the houses that had once rung with the

licentious revelry of Morgan - who, by the way, received the honor of

knighthood - and his fellow sea-robbers, could be seen as monuments of

God's judgments. In this region, where there is no twilight, but the sun

sets and darkness succeeds, all the objects in the harbor were fading

into gloom, though St Catherine's Peak and the summits of some of other

mountains were yet gilded with the rays of the departing sun, as we cast

anchor.

NUMBER III

Description

of Kingston - Inhabitants - Amalgamation of the Races - Effects of

Emancipation - Jamaica Politics - House of Assembly - Soil, Climate,

Products, &c., &c.

Kingston, Jamaica, Nov. 17.

Whatever

of romance may be awakened by a first view of Kingston Bay from the

sea, is very soon dissipated on landing. The town is laid out well

enough, on the rectangular plan, but the streets are all narrow - from

ten or twelve feet to two or three rods wide; even Port Royal and Harbor

streets, once so renowned for their wealth and business, are not wider -

none are paved or graded, and none rejoice in the luxury of a sidewalk.

None of the houses display any architectural taste They are all low - I

have seen none more than two stories high, and most of them are only

one - built of brick with wooden verandahs, in front and rear, enclosed

by windows and strong heavy jalousies. These wooden appurtenances are

very comfortable, as I can testify by experience, but for the most part

they need painting, and give the streets a decaying, dilapidated look. A

visitor from the northern States, when he first walks through the town,

feels very uncomfortable; for in consequence of the narrowness and

neglected condition of the streets, and the universal style of building I

have described, he cannot at first divest himself of the feeling that

he is skulking through lanes and alleys in the rear of gentlemen's

houses, or is walking through some miserable, degraded quarter of our

cities, where it would be dangerous to go after nightfall. The swarms of

negroes and colored people in the streets heighten this feeling. Of the

forty or fifty thousand inhabitants Kingston is supposed to contain,

eight-tenths, and I am not sure that it would not be safe to say a

greater proportion, are black or colored. The whites are so few they

seem to be intruders. The colored people - including under that term

blacks, mulattoes, and all with a mixture of African blood in their

veins - are not only the loafers, laborers and servants, but you see

them in the shops, in the public offices, in the counting rooms of

merchants, in short in every place of trust and responsibility.

Politically and socially they are on the level of perfect equality with

the whites. The finest equippage I have seen in Kingston was an open

landau, drawn by two spirited bay horses, with good blood in their

veins, evidently, and driven by a black fellow in a smart livery. On the

back seat, languidly reclined two colored ladies, dressed in the height

of Parisian fashion. This turn-out drew up at the door of one of the

prominent shops, or stores as we would say, and the white shop-keeper

waited with the utmost attention and deference upon the ladies, who,

without getting out, inspected his wares, made their purchases and drove

off. At St James's church - the oldest on the island - last Sunday,

more than three quarters the congregation were colored, among whom, as

if by privilege, the whites were seated indiscriminately. It was

communion day, and the curate informs me that of the whole number of

communicants - between four and five hundred - more than three quarters

were colored. In the House of Assembly there are about a dozen black aud

colored members. In Spanishtown, the capital of Jamaica, I saw last

week several of them in their places. Two or three were jet black.

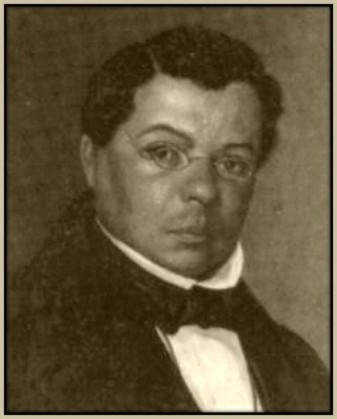

I did not hear them speak, but one colored man, Mr Osborn - publisher of the Morning Journal,

a widely circulated and influential paper of this city - took a

prominent part in the business of the House showing a thorough

acquaintance with Parliamentary usage and the rules of the House, and

speaking with great readiness and fluency. The Speaker told me that he

was really a man of decided ability.

The result of all this, it is obvious enough, will be the complete amalgamation of the two races. Indeed it is already going on very rapidly. I will not here offer any speculations on the probable effect of amalgamation; my object now is simply to give facts. I am bound to say, however, that so far from witnessing the license and disorder alleged, by gentlemen of other islands to exist in consequence of emancipation, I never saw in a town of the same population as this, more good order and external propriety of deportment. The negroes are uniformly civil. I have not yet seen a drunken man or a street brawl, nor heard any foul language. The streets are remarkably quiet after night fall. All the shops are shut up at sunset and at eight or nine o'clock the town is as still as our cities are at midnight. But it is said the negroes will not work, now they are free, and from country gentlemen, commercial men, every body almost, you will have the most deplorable accounts of the condition of the island, of the want of money, of the giving-up of once most valuable estates in consequence of the cost of working them, and the low price of produce, of the falling off of exports and business, &c., &c. All this may be true, though I suspect somewhat exaggerated; but that which should influence our judgment in deciding for or against emancipation and its consequences, is this: Are the colored population - who constitute so large a majority of the whole population of the island, and who, under any circumstances, in all human probability, will and must continue to do so - better off, morally and intellectually, and in their material comforts, in a state of freedom, such as they now enjoy, than in a state of slavery? If yea, then no more is to be said; for, however much we may deplore the individual loss and suffering of the planters, we must confess that the improved condition of the great mass of the people, the peasantry, and the prospect of their moral and intellectual elevation is a satisfactory equivalent. That the condition of the colored population has been improved is confessed by all with whom I have conversed on the subject; clergymen, magistrates, public officers, planters, commercial men, all without any exception agree on this point. But, say many of them, the negroes are too well off. The climate is so genial and the soil so fruitful that an acre or two of ground, even slightly cultivated, will supply all the wants of a negro family, so far as mere subsistence is concerned. A few days labor beside will provide the necessary clothing, and ensure the finery, he and his family may require, and the result is that, instead of working four or five days out of seven, he will now work but one, for which he demands a high price, and the estates once so profitable cannot now be worked in competition with the slave-worked estates of Cuba and Brazil.

This is undoubtedly true, and Great Britain, after freeing the slaves in her colonies, in obedience, as was said to a high principle, was bound by the same principle not to admit the slave products of Cuba and Brazil on the same terms with the free products of Jamaica. But if John Bull loves to make a grand display of philanthropy and conscientiousness, he loves cheap sugar at the same time; and having done a highly virtuous act, as he conceived, in freeing his slaves, he thought that, like a good boy, he deserved a sugar plum for his good conduct. All argue that Jamaica would have prospered, if the protective duty, that was promised when the emancipation act was passed, had been continued. But it has been taken off, and with the high prices of labor that now rule in the Island, it costs more to make a sugar crop than it will sell for in market. But is it necessary, I asked of the gentlemen with whom I conversed, to think of sugar and rum altogether? Can you not, in an Island so fertile, so abounding in natural resources, turn your attention to some other pursuits, and so diversify your industry? You import all your pork and beef from the States. Nothing is easier than to raise hogs and cattle on your mountains. Indian corn would flourish luxuriantly. The soil is admirably adapted to the culture of the cocoa nut tree. - Why not extend its cultivation? To these and a hundred other suggestions of like character, the reply is we have no money. The merchants at home will advance us no money now, and we are ruined.

In this reply will be found, as I conceive, the key to most of the troubles of Jamaica. The planters have no money, because, in the days when money was plenty, they lived extravagantly - all, with scarcely an exception, up to their incomes, and many beyond. In many instances, too, the proprietors of estates lived in England, or wintered there to spend their means. When the Emancipation act was passed, most of the estates were in debt, and the compensation the planters received for their slaves went to pay these debts, and left them without the capital necessary under the new state of things. The word "home" has caused a deal of mischief to the island, by inculcating and perpetuating the idea among the planters and business men, that they were merely sojourners in Jamaica for so long a time only, as would suffice to accumulate a competency wherewith to return to England or Scotland. Nobody seemed to consider Jamaica as home. The effect of this feeling is visible in Kingston, where, notwithstanding its great commercial importance for the last one hundred and fifty years, there is not a single monument to indicate to the stranger its great commerce and wealth. Its public buildings are mean, its streets, as I have said, are unpaved and utterly neglected, its wharves are a disgrace to it; everything, in short, indicates that no one feels as if he were to reside here permanently, but was only anxious to get what he can, and then go away. The Imperial Government, doubtless for what was considered wise and sufficient reasons, has adopted a certain line of policy, that bears very hard on Jamaica. The island may have good cause to complain of injustice - and her case is peculiarly hard, for, unlike Canada, now on the verge of revolution, Jamaica, instead of being a burden to Great Britain, pays her own expenses, all the enormous salaries of her officials, who are sent out from England, and even pays part of the expenses of the military establishment, beside making a large annual grant to the British crown. But what can she do? It can hardly be expected that the Imperial policy will be altered to suit the interests of a colony like this. Nothing then remains but to look the condition of things boldly in the face, make the best of such condition, and instead of talking and thinking about "home," consider Jamaica as home.

Unhappily, the Governor and Council on the one hand, and the House of Assembly on the other, have got at loggerheads, and there has been such an exchange of compliments between them - formally reviewing, in critical, argumentative and satirical resolutions, each other's proceedings, and exclaiming breach of privilege when a pungent hit told - as in any other country would lead to the apprehension of very serious consequences. What will be the result it is difficult to say, but it is evident that, by reason of these contentions, whichever party is in the wrong, the Island suffers, and in the meantime men's minds get heated by partisanship and faction, and the prospect of reconciliation and co-operation in mutual endeavors to promote the public weal, becomes more and more remote. I might dwell at much length on this subject, but I fear Jamaica politics would weary my readers.

The Island is a noble one. Its soil is unsurpassed for fertility. Almost every thing that grows in the tropics, either of this continent or Asia, will thrive here. Its climate, though warm, is equable and healthy. In examining yesterday some meteorological tables, I found that the mean of the thermometer for every month in the year in this city is about 80⁰ of Fahrenheit. In the mountains one can have almost such a climate as he likes. Some of the peaks of the Blue Mountains are more than eight thousand feet high, and the whole Island is diversified by mountainous ranges of greater or less elevation. In this Jamaica proffers to the invalid advantages over every other Island of the West Indies. Nothing an exceed the beauty of this mountain scenery, which will delight the eye and imagination, while roaming among it will give health to the body. - Living in the country is cheap, the physicians are well educated in their profession, and the inhabitants are hospitable and well disposed to Americans. Just now there is a remarkably good feeling toward our country, and as a mark of this, I may here mention that a few days ago, by special law, the Legislature gave, to the American line of steamers to Chagres, the same privileges that are accorded to the steamers of the Royal Mail Company. The Flora of the Island is very rich, and in natural history, generally, no more attractive field is offered any where than in Jamaica. The country abounds with birds of a great variety of genera, and, which is unusual in a tropical country, many of them are delightful songsters. I do not remember when, even in a May or June morning in the States, I have heard the air more vocal with the sweet singing of birds, than it was a few mornings since when I was returning from Spanishtown. The sun was shining brightly, but a pretty heavy shower the night before and the rising sea breeze cooled the air, which was in truth, filled with perfume, and from the luxuriant vegetation on either side of the road thousands of tuneful throats uttered their notes of joy. The wild boar is said to exist in the mountains. It is probably a descendant of the common hog, brought here by the early settlers; but intelligent gentlemen aver that it is a distinct species from even the Alligator or Land Pike, so abhorred by my friend, Allen, of Black Rock; but I doubt. However that may be, the animal affords good sport to the hunter, and is sufficiently dangerous, when hard pressed, to render his pursuit exciting. Snakes are found, some of large size, but none venomous; indeed venomous reptiles of every kind are very rare, if not altogether unknown.

NUMBER IV.

Sources of wealth of Jamaica - Call upon Santa Anna - Institutions - Salaries of Officers - The Capital - Military force of the Island - Religion - The Penitentiary - The Earthquake of 1692 - Impressions on leaving - &c., &c.

Kingston, Jamaica, Nov. 18.

Jamaica, among other sources of wealth, is rich in valuable and beautiful woods. I saw in a cabinet-maker's shop, a few days ago, some twenty or more specimens of various woods, suitable for furniture and cabinet work, that in texture, variety of tints, and the polish they would receive, would not suffer in comparison with the choicest woods of foreign or native growth used in our country. These woods can be purchased very cheap - though furniture is costly here - and some of them are peculiar to the island. Mahogany is yet quite plenty on the island, but not generally of the most esteemed kind. Ebony I have seen piled up on the railway wharf, like cord wood. Years ago, in the days of great prosperity, when gold and silver were shovelled into barrows and wheeled through Harbor and Port Royal streets, an ambitious man would occasionally lavish great expense on his house, poor as most of the dwellings look from the street.

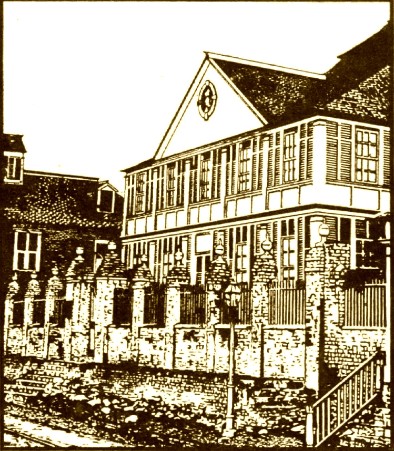

The

house where I am staying, known as Date Tree Hall, from a large date

tree growing in front of it, is a specimen of this kind. It was built by

a merchant for his own residence, and cost fifty thousand dollars. It

is two stories high. A hall, some twenty five feet wide, by fifteen

high, runs through both stories, opening upon verandahs in front and

rear, and on each side of these halls are sleeping rooms of ample

dimensions.

The doors, and the casings of the doors and windows, the

window blinds, the entire staircases, indeed most of the woodwork, is of

solid mahogany of the most beautiful kind. The floors, innocent of

carpets - which, in a climate like this, would be intolerable - are

polished like glass. Meals are served in the verandahs, changing from

one to the other to avoid the sun. Surrounding a court in the rear, are

the offices of the house, servants apartments, stables, &c. This is

the general style of all the good houses I have seen, but, of course

most of them are built at much less cost than the one I have described.

The handsomest house, externally, I have seen in Kingston or its

environs, and the most like a gentleman's mansion within, according to

northern notions, is the one occupied by Gen. Santa Anna, about two

miles out of town on a road affording a charming drive. I saw it and its

occupant, by accident, last Sunday evening. I was riding with the

Attorney General of the island, to whom I am greatly indebted for his

kind and courteous attentions, when, as we drew near a house of good

size and style, surrounded by grounds nicely kept, he asked me if I knew

Santa Anna. On my replying in the negative, he inquired if i would like

to see him, and almost without waiting for an answer, turned into the

open gate-way and up the broad carriage road to the door. On alighting,

we were ushered into a large drawing-room, neatly furnished, and in a

few moments Santa Anna, accompanied by his wife and daughter, joined us.

I was disappointed in his appearance. He is taller and stouter than I

had supposed, and there is much grace and even dignity in his carriage.

His manner was bland and courteous, but grave. Our intercourse was

confined to the merest commonplaces, for he had but little English and I

less Spanish at command. Madame Santa Anna, of whose beauty I had often

heard, is worthy all the encomiums she has received. Her figure is

exquisitely moulded, plump to the extremest point consistent with

perfect health, grace of motion and symmetry. Her complexion is of the

cool, opaque white, peculiar, I believe to the thorough-bred Spanish

women. If her eyes, which are black and sparkling, were a trifle larger,

and relieved by a slightly increased depth of shade, so as to

correspond more strictly to the classical outline of her head and face,

she would be one of the most beautiful women I have seen. She speaks

English very well, and her manner is exceedingly lady-like, frank and

gracious.

I have too little time and space in which to speak as I would like to

do of some of the institu lions of the Island and matters connected

therewith. The Legislative power of the Island is vested in the Governor

and Council and House of Assembly. The members of the Council are

appointed for no specific term, but hold office during good behavior,

or, to use the words of a prominent member of the House fond of making

nice distinctions, during pleasure. Many of the present Council hold

high official stations beside, as the Chief Justice, the Major General

commanding the forces, the Attorney General, &c., from which, with

the exception of the last named, they derive large salaries. These

salaries were fixed when the colony was prosperous and money abundant,

and now, when every body is complaining of poverty, they are thought to

be excessive. There is some reason for this complaint. -The Chief

Justice gets $15,000 a year; the Receiver General the same, and many

other officers receive salaries which it is said the island cannot

afford to pay. A bill was lately passed by the House cutting them down,

but the Council threw it out, and a deal of ill blood is the

consequence. The House, like the English Commons, is chosen

septennially, and like the Commons is subject to be dissolved by

authority. The Governor, however, after dissolving one House, cannot

dissolve the one chosen in its place, and this fact renders the existing

state of things very embarrassing. The House preceding the present one

was dissolved, so the Executive power can do nothing with the refractory

members, now in the opposition, and constituting the majority, unless

authorised to act by the Imperial Government - Sir Charles Grey, the

Governor, enjoys great personal popularity; even the country party are

constrained to speak well of him as a man, but is far from being

favorably regarded officially. He is a civilian, and served a long time

as Judge in India. In the frank simplicity of his manners and his

general bearing he strongly reminded one of the late Gen. Peter B

Porter.

Spanishtown, the capital, was known in former times as St Jago de la

Vega. It is almost twelve miles from Kingston, and communication is had

with it by means of a railway, that some English capitalists, a few

years ago, when they could not find vent for their surplus means in

English railways, undertook to construct to the North side of the

island. Its whole length is only sixteen miles, and it will probably

never be any longer, as it hardly pays the cost of working,

superintendence and repairs. The capital is a miserable, dilapidated

looking place, and but for the fact that the government offices are

there would soon be altogether deserted. The plaza, or grand square,

however, makes a very respectable appearance, and displays more

architectural pretension than I have seen elsewhere in Jamaica. King's

House, as the Governor's residence is termed, occupies one side of the

square. It is a staid, rather heavy building, of large size, but such of

its apartments as I have seen are comfortable, and some of them

handsome in their proportions and finish. The building on the opposing

side of the square - which is well stocked with trees and shrubs, but

greatly neglected - is occupied by the House of Assembly, and is

conveniently divided into Legislative Hall, Committee Rooms, Library,

&c. The library is very meagre, containing next to nothing in regard

to the early history of the island, except what may be buried in

ponderous volumes of documents and journals. On the North side is a

Grecian temple enclosing a statue of Lord Rodney, erected by Jamaica in

gratitude for his victory over the French fleet near the close of our

Revolutionary War. I cannot, in conscience, say much in favor of the

temple or statue as works of art.

The military force of the island is composed of about 5,000 men, 2,000

of whom, or thereabouts, are Africans, captured from slavers. They are

really fine looking fellows, straight, well set up, and in a high state

of discipline. All their commissioned officers are white, who say their

men understand no nonsense, but if directed to suppress any disorder do

so at once, and with the bayonet, or ball cartridge. They know nothing

of moral suasion.

The religion of the Church of England is by law established. Until

recently the island constituted part of the diocese of the Bishop of

London. Now it is a Bishopric by itself. The Clergy, for the most part,

are well paid. The Rector of St. James in this city, receives $1,000 a

year, and is assisted by two Curates. One quarter of the entire

population of the island, perhaps, professes the faith of the Church of

England. The Roman Catholics, Baptists, Wesleyan Methodists, Scotch

Presbyterians, Independents, &c., divide the remainder.

One of the most interesting objects to a visitor here, and one most

worthy of his attention is the Penitentiary. With emancipation came a

large increase of criminal convictions. This fact should not be taken as

evidence of increased demoralization as the consequence of freedom, for

before emancipation the thousand cases of larceny and assault which

were the most common offences, were summarily settled by flogging the

offenders. Now the courts take cognizance of all such matters, and the

criminal record is greatly enlarged. What to do with the criminals was

an object painful solicitude, inasmuch as they could not be sent out of

the country, and a system of discipline adapted to the character of the

blacks, with their low scale of moral and intellectual culture was not

easily framed. The punishment by the lash was abrogated, for that was

thought to savor too much of the old times of slavery. To shut up a

Negro in his cell was no great punishment, for, as he was not denied

food, he would lie down and sleep very contentedly. Appeals to their

moral nature seemed thrown away. In addition to all this was another

serious difficulty resulting from the impoverished condition of the

public finances and the fact that the prisoners could not be profitably

employed. The accomplished Superintendent, Mr Daughtrey, has done all he

could to conquer these difficulties. He visited the States and

inspected our prisons with a view to adopt such portions of our systems

as were suited for this island, but better times must come before the

prison can be made all it should be. It is kept remarkably neat, is

healthy, and very soon, on the completion of buildings now in process of

erection, each prisoner will have a separate cell, and the solitary

system, so far as it is enforced in some of our prisons, Auburn, for

instance, will be carried out here. The abolition of the lash I cannot

but think a sacrifice to a spirit of mistaken philanthropy, and the

large number of convicts serving out sentences for second and third

offences, shows that the Penitentiary is not regarded with great horror.

It is a pity the Town Council of Kingston will not employ them in

grading and paving the streets. The entire number is between four and

five hundred.

One of the things that arrests a strangers attention in walking about

town, is the multitude of old cannon he sees in the streets. They are

planted as posts in the ground at every corner of the streets. I counted

twenty in Port Royal street this morning, in walking ten rods. They are

mostly weather-beaten and worm-eaten, but to my eye they have a very

grim and savage look; for if they could speak, what a tale would they

tell of desperate piracy and buccaneering? Some of them are English

guns, condemned as unfit for use; but many of them were captured from

the Spaniards, or from pirates hung at the yard-arm at Port Royal.

The mention of this place and its association with the terrible

earthquake of 1692, reminds me of the fact that this island is quite

subject even now to slight trembling of the earth, though no serious

damage has been done for many years. They are frequent and severe

enough, however, to remind the dwellers of the fearful forces that

slumber beneath them. I had thought but little on the subject, scarcely

remembering, in fact, that such things as earthquakes could be, but was

strongly reminded of the reality of their occurrence by the

interpolation in the litany of "From lightning and tempest, and

earthquake," last Sunday morning. The anniversary of the destruction of

Port Royal is observed throughout the island as a day of fasting and

prayer.

The steamer from England came in yesterday, and tomorrow at 8 o'clock I

sail in the good ship Avon for Santa Martha, on the Spanish Main. I

shall leave Kingston with much regret, for I have found here friends

whose kindness and attentions have made my sojourn one of the most

agreeable passages in my life. One, too, soon acquires a love for even

the inanimate objects by which he is surrounded, if of an agreeable

nature. As I lift my eyes from the paper, tall cocoa trees are

gracefully waving in the cooling sea breeze - by the way, why will not

artists adopt the cocoa-nut with its sweeping, picturesque, plume-like

foliage, instead of the comparatively stiff, angular and naked date as

their conventional type of the palm? -the air is fragrant, masses of

clouds are gathering about the summits of the most distant mountains,

the temperature is like the warmest weather of our July, and nature, so

rigorous with us, here, in all its aspects, heightens man's enjoyments

But, alas, I cannot even thus cheat myself out of the recollections of

home. Good bye.