1835 - Penny Magazine

The Penny magazine of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge,

Volume 4,

Charles Knight, Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (Great Britain), 1835

Kingston is the principal commercial town, and actual capital, of Jamaica although the seat of is at S. Jago de la Vega, or Spanish Town, about ten miles inland. Kingston was founded in 1693, the after that most awful earthquake by which the was shaken to its centre, and the town of Port Royal was destroyed with 2000 of its inhabitants. The survivors thought it would be better to establish elsewhere, and the site of Kingston was selected most suitable for their purpose.

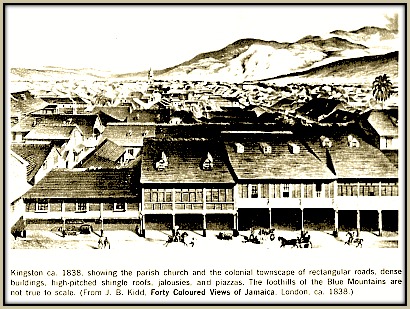

Kingston is situated upon a gentle slope, which is about one mile in length, and is bounded on the south by a spacious basin through which all vessels must advance under the commanding batteries of Port Royal. The extended inclined plane, upon the verge of which Kingston stands, is enclosed on the north by the loftiest ridge of the Blue Mountain chain, termed Liguanea, which rises to the height of near 5000 feet at the distance of four miles behind the town. This ridge forms a semicircle, which terminates in the east at the narrow defile of Rock Fort, from whence a long neck of land stretches far away to Port Royal, forming the southern barrier of the excellent haven. The semicircle terminates in the west at a narrow pass, upon the edge of an impracticable lagoon, from whence the main-land sweeping round Port Henderson and the projecting salt-pond hills secure one of the most superb mercantile havens in the world, and in which the whole navy of England might commodiously and safely ride. The entrance of this harbour is defended on the east point of the delta of Port Royal, by the formidable ramparts of Fort Charles, and on the west side by the cannon of Rock Fort, while the low raking shot from the sixty pieces of large cannon on the long, level lines of Fort Augusta would blow a hostile navy out of the water before it could pass the narrows to get up to the anchorage at Kingston. To the above statement, which incorporates the accounts of Mr. Montgomery Martin and Captain Basil Hall, the latter, a most competent judge on such points, adds that the haven is completely land-locked; and, even independently its fortifications, may be deemed almost impregnable towards the sea, as it would be little short of a miracle for an invading squadron to wind its way through the labyrinth of shoals and reefs which lie off its mouth, and among which the channels are so narrow and intricate, that the sinking of a sand barge would effectually block up all ingress.

The situation of Kingston is highly favourable, rising from the sea with sufficient acclivity to give it the command of the sea breezes, which blow regularly during the greater part of the year, and also to afford a view of the ships coming down the coast to the harbour of Port Royal and up to the town. Dr Madden describes two views of the town - one from the mountains and another from the sea, which exceed anything that can be imagined by one who has not seen Constantinople from the sea-side, and Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives. The distance between the town and the mountains is pleasingly diversified with country residences, and, near the mountains, with sugar estates. The dryness of the soil on which the town stands, together with the slope, prevents any inconvenience from the lodgment of water in the heaviest rains, while the town is well ventilated by the daily sea-breeze. But although the slope prevents any water from stagnating in the town, it is attended with one great inconvenience, for it admits an easy passage to great torrents, which collect in the gullies, at some distance towards the mountains, after a heavy rain, and sometimes rush so impetuously down the principal streets as to make them almost impassable by wheel-carriages, and carry accumulations of mud and rubbish to the wharfs. The front foundations are undermined by the same cause, in consequence of which many the houses have a shattered appearance, which in some measure gives to the town the aspect of a ruined city.

The original plan of the town, as drawn out by Colonel Lilly, an experienced engineer, was a parallelogram, one mile in length by half a mile in breadth, regularly traversed by streets and lanes, crossing each other at right angles, except at the upper part, where a large square was left; but the town has now extended so far beyond the limits assigned it in this plan, that the square is at present nearly in the centre of the city. The streets in Lower Kingston are long and straight, and laid out with a regularity which Martin compares to that of the new town at Edinburgh. Here, of course, the comparison ends. The houses are generally built of brick, and are two stories high, having the fronts shaded by a piazza below and a covered gallery above. The English and Scotch churches are, perhaps, the most elegant structures in the town, particularly the former, which is built on a picturesque spot, commanding a splendid view of the city, the plains around it, the amphitheatre of mountains, and the noble harbour. The church itself is a large and elegant building, with four aisles, and having a well-constructed tower and spire, which form a great ornament to the town. The other public buildings are the court-house, a free-school, a theatre, the barracks, the public jail, and an asylum for deserted negroes.

Captain Basil Hall in his 'Tom Cringle' has described the town in his usual happy manner. We shall therefore give his account of it in his own words. He says -

"The appearance of the town itself was novel and pleasing; the houses, mostly of two stories, looked as if they had been built with cards, most of them being surrounded with piazzas, from ten to fourteen feet wide, gaily painted with green and white, and formed by the roofs projecting beyond the brick walls or shells of the houses. On the ground-floor, these piazzas are open; and in the lower part of the town, where the houses are built contiguous to each other, they form a covered way, affording a most grateful shelter from the sun on each side of the streets, which last are unpaved, and more like dry water-courses than thoroughfares in a Christian town. On the floor above, the balconies are shut in with a sort of movable blind called "jealousies," like large-bladed Venetian blinds fixed in frames, with here and there a glazed sash to admit light in bad weather, when the blinds are closed. In the upper part of the town the effect is very beautiful, every house standing detached from its neighbour in its little garden, filled with vines, fruit trees, and stately palms and cocoa-nut trees, with a court of negro-houses and offices behind, and a patriarchal-looking draw-well in the centre, generally overshadowed by a magnificent wild tamarind."

The same writer describes a walk through "the burning, sandy streets" as an exceedingly unpleasant affair, particularly as one is almost blinded by the reflection from them. He also favours us with an introduction to the interior of the houses, informing us that carpets are not in use in Jamaica; but the floors, which are often of mahogany, are beautifully polished, and shine like a well-kept dinner-table. They are, however, attended with the disadvantage of being very slippery, and require wary walking till one gets accustomed to them.

Accidents from fire rarely occur in Kingston, the kitchens being detached buildings, and there are wells and pumps in the principal streets. Fire-engines and leather buckets are also kept in the court-house, and the inhabitants are obliged to keep a certain number of these buckets proportioned to the value of their houses. The fate of Port-Royal, of Bridge Town in Barbadoes, and of St. John in Antigua, awfully inculcated the necessity of the strictest precautions against the ravages of accidental or incendiary fires.

In the hottest part of the year the thermometer at Kingston sometimes rises as high as 96⁰, and is seldom below 76⁰. It is generally three degrees warmer than Spanish Town, and the air is less elastic, but it is not equally subject to thunder- storms. Notwithstanding the great heat of the climate, Bryan Edwards assures us "on the information of a learned and ingenious friend, who kept comparative registers of mortality, that since the surrounding country has become cleared of wood, the town is found to be as healthful as any in Europe." The market-place of Kingston is in the lower part of the town, near the water-side. It is plentifully supplied with butchers' meat, poultry, turtle, fish, fruits, and vegetables. In the last class it not only offers the products usually found in a tropical country, but also European vegetables, which one would hardly expect to find there, such as pease, beans, cabbage, lettuce, cucumbers, artichokes of the finest kind, carrots, turnips, radishes, onions, leeks, and small salad. These are brought from the Liguanea mountains, and are all excellent of their kind. Here also are strawberries, not inferior to those produced in an English garden; and very good apples, but in general gathered before they are ripe. Large quantities of the finest pine-apples are also produced, particularly on the Long Mountain. "In short," says the enraptured historian of Jamaica, "the most luxurious epicure cannot fail of meeting here with sufficient in quantity, variety, and excellence for the gratification of his appetite all the year round." For these advantages, however, it seems that the said epicure must pay a good price. Dr. Madden, the most recent writer on Jamaica, believes it to be the dearest country in the world.

There is a sad want of statistical facts, not only concerning Kingston, but Jamaica in general. The population of the city is roundly estimated at 35,000, of whom 10,000 are whites, 17,000 negro apprentices (lately slaves), and the rest creoles and free people of colour. Kingston was incorporated as a city in 1803; and is governed by a mayor, twelve aldermen, and twelve common-councilmen.